Steve Meretzky was a boundless fount of creative energy which couldn’t be contained by even his official projects for Infocom, many and varied as they were, and spilled over into daily life around the office in the form of elaborate themed parties, games that ranged from a multiplayer networked version of Boggle played over the DEC minicomputer to intense Diplomacy campaigns, and endless practical jokes. (“Memo hacking” became a particular favorite as Business Products ramped up and more and more buttoned-down business types started to appear in the office.) The lore and legends of daily life at Infocom, eagerly devoured by the faithful via the New Zork Times newsletter, is largely the lore and legends of Steve Meretzky, instigator and ringleader behind so much of the inspired lunacy.

Yet there was also another, oddly left-brained side to Meretzky. He was a compulsive organizer and even a bit of a neat freak; his meticulous and breathtakingly thorough archives informed much of Jason Scott’s Get Lamp project and, by extension, much of the Infocom history on this site. Mike Dornbrook, Infocom’s marketing director, calls Meretzky the most productive creative person he has ever met, one who evinced not a trace of the existential angst that normally accompanies the artistic temperament. Writer’s block was absolutely unknown to him; he could just “turn it on” and pour out work, regardless of what was happening around him or how things stood in his personal life.

But there was still another trait that made Meretzky the dream employee of any manager of creative types: he was literally just happy to be at Infocom, thrilled to be out of a career in construction management and happy to work on whatever project needed him. And so when Dave Lebling decided he’d like to write a mystery game and Marc Blank wanted to work on technology development, leaving the critical second game in the Enchanter trilogy without an author, Meretzky cheerfully agreed to take it on. When a certain famous but mercurial and intimidating author of science-fiction comedies came calling and everyone else shied away from collaborating with him, Meretzky said sure, sounds like fun. And when Tor Books offered Infocom the chance to make a series of Zork books in the mold of the absurdly successful Choose Your Own Adventure line, and everyone on the creative staff turned up their noses at such a lowbrow project even as management rubbed their hands in glee at the dollar figures involved, Meretzky took the whole series on as his moonlighting gig, cranking out four books that were hardly great literature but were better than they needed to be. Most gratifyingly of all, Meretzky ripped through all of these projects in a bare fifteen months whilst offering advice and ideas for other projects and, yes, getting up to all that craziness that New Zork Times readers came to know and cherish. Meretzky was truly a dream employee — and a dream colleague. One senses that if management had asked him to go back to testing after finishing Planetfall he would have just smiled and kicked ass at it.

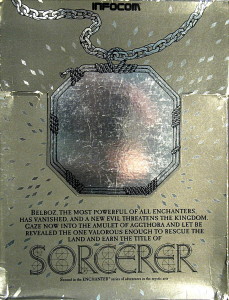

Sorcerer, his sequel to Enchanter and Infocom’s first game of 1984, was, like so much of Meretzky’s work in this period, a bit of a thankless task. He neither got to devise the overarching plot and mechanics for the trilogy nor to bring things to a real conclusion, merely to write the bridge between fresh beginning and grand climax. Middle works in trilogies have always tended to be problematic for this very reason, and, indeed, Sorcerer is generally the most lightly regarded of the Enchanter games. I won’t really argue with that opinion, but I will say that Sorcerer is a very solid, entertaining work in its own right. It’s just that it gets a bit overshadowed by its towering companions, together arguably the best purely traditional adventure games ever to come out of Infocom, while also lacking the literary and thematic innovations that make games like Planetfall and Infidel — to neither of which it’s actually markedly inferior in overall quality — so interesting for people like me to write about.

Sorcerer casts you as the same budding enchanter you played in the game of that name. Having vanquished Krill, however, your star has risen considerably; you are now a member of magic’s innermost circle, the Circle of Enchanters, and protege of the Leader of the Circle, Belboz. Sorcerer opens with one of its most indelibly Meretzkian sequences. You are snug in your bed inside the Guild of Enchanters — but you don’t actually realize that for a few turns.

You are in a strange location, but you cannot remember how you got here. Everything is hazy, as though viewed through a gauze...

Twisted Forest

You are on a path through a blighted forest. The trees are sickly, and there is no undergrowth at all. One tree here looks climbable. The path, which ends here, continues to the northeast.

A hellhound is racing straight toward you, its open jaws displaying rows of razor-sharp teeth.

>climb tree

Tree Branch

You are on a large gnarled branch of an old and twisted tree.

A giant boa constrictor is slithering along the branch toward you!

The hellhound leaps madly about the base of the tree, gnashing its jaws.

>i

You are empty-handed.

The snake begins wrapping itself around your torso, squeezing the life out of you...

...and a moment later you wake up in a cold sweat and realize you've been dreaming.

SORCERER: INTERLOGIC Fantasy

Copyright (c) 1984 by Infocom, Inc. All rights reserved.

SORCERER and INTERLOGIC are trademarks of Infocom, Inc.

Release 4 / Serial number 840131

Your frotz spell seems to have worn off during the night, and it is now pitch black.

Like the similarly dynamic openings of Starcross and Planetfall, albeit on a more modest scale, Sorcerer‘s dream sequence can be a bit of a misnomer. The rest of the game is much more open-ended and much less plot-driven than this sequence might imply. As you explore the conveniently deserted Guild — everyone except you and Belboz have gone into town to shop for the Guild picnic — you soon realize that Belboz has mysteriously disappeared. And so the game is on, fueled by the same sort of magic-based puzzles that served Enchanter so well. Indeed, Meretzky copied the code for the Enchanter magic system wholesale into Sorcerer, along with some of the same spells, which had to be a great help for someone working on as tight a timetable as he was. Sorcerer‘s one big magical innovation is a set of potions to accompany its spell scrolls, something notably absent not only from Enchanter but also from Lebling’s Spellbreaker, the final game of the trilogy.

Like all of the Enchanter trilogy a very traditional game, Sorcerer is divided into two open-ended areas of exploration, the Guild of Enchanters and a sprawling wilderness and underground map which ultimately proves to house Belboz’s abductor, the demon Jeearr (another thoroughly Meretzkian name, and a character who also turns up in the last of the Zork gamebooks he was writing at the same time). The overall feel is looser than Enchanter, with the first game’s understated humor replaced with a more gonzo sensibility that can rub some players the wrong way. This player, who felt that Planetfall often seemed to be trying just a bit too hard, doesn’t exactly find Sorcerer hilarious but never really found it irritating in the way that Meretzky’s earlier game could occasionally be either. Perhaps the fact that Sorcerer wasn’t explicitly billed as a comedy left Meretzky feeling freer not to force the issue at every possible juncture.

Another Planetfall trait, that of lots of Easter eggs and red herrings, is also notable in Sorcerer, but again to a lesser extent. The useless bits, such as a functioning log flume and roller coaster inside the amusement park inexplicably located almost next door to Jeearr’s infernal lair, are mostly good fun. The sadomasochistic “potion of exquisite torture” is a standout that is just a bit risque for the prudish world of adventure gaming:

>drink indigo potion

The potion tastes like a combination of anchovies, prune juice, and garlic powder. As you finish swallowing the potion, a well-muscled troll saunters in. He whacks your head with a wooden two-by-four, grunting "You are playing Sorcerer. It was written by S. Eric Meretzky. You will have fun and enjoy yourself." He repeats this action 999 more times, then vanishes without a trace.

Another great bit comes if you use the aimfiz spell — “transport caster to someone else’s location” — to try to find Meretzky himself:

>cast aimfiz on meretzky

As you cast the spell, the moldy scroll vanishes!

You appear on a road in a far-off province called Cambridge. As you begin choking on the polluted air, a mugger stabs you in the back with a knife. A moment later, a wild-eyed motorist plows over you.

**** You have died ****

Like any old-school adventure game, Sorcerer is full of goofy and often random ways to die, from wandering into a room that’s missing a floor to getting buried under coins by an overenthusiastic slot machine. Still, Meretzky manages to skirt the letter if not quite the spirit of Andrew Plotkin’s Cruelty Scale through the gaspar spell: “provide for your own resurrection.” Gaspar returns you upon your death alive and well to the place where you last cast it, a handy substitute for the technological rather than arcane solution of restoring a saved game. If nothing else, its presence proves that Infocom was thinking about the arbitrary cruelty of most adventure games and wondering if a friendlier approach might be possible. (Space limitations would, however, always limit how far they could travel down this path. It would always be easier to simply kill the player than try to implement the full consequences of a bad — or simply unplanned for — decision.) Another sign of evolving thought on design comes in the form of the berzio potion (“obviate need for food or drink”), which slyly lets you bid adieu to the hunger and thirst timers of Enchanter and Planetfall. A year later, Spellbreaker would not even bother you with the whole tedious concept at all.

As the presence of amusement parks and casinos next to abducted enchanters and demons would imply, Sorcerer doesn’t concern itself at all with the fictional consistency that marked Planetfall or even, for that matter, Enchanter. Plot also takes a back seat for most of the game. You simply explore and solve puzzles until you suddenly bump into Jeearr and remember why you’re here. Likewise, some of the writing is a bit perfunctory if we insist on viewing Sorcerer as a literary experience. That, however, is not its real strength.

I find Meretzky slightly overrated as a writer but considerably underrated as a master of interlocking puzzle design. Sorcerer is full of clever puzzles, one of which, a relatively small part of the brilliant time-travel sequence in the coal mine, represents the last little bit of content which Infocom salvaged from the remaining scraps of the original MIT Zork. Yet it isn’t even one of the most memorable puzzles in Sorcerer; those are all Meretzky originals. In addition to that superb time-travel puzzle, there’s a fascinating thing that seems to be a maze but isn’t — quite. Both time-travel puzzles and pseudo-mazes were already burgeoning traditions at Infocom; both would remain obsessions of the Imps for years to come. Meretzky does both traditions proud here. I won’t say too much more about Sorcerer‘s puzzles simply because you really should enjoy them for yourself if you haven’t already. They’re always entertaining, clever, and (sudden deaths and one tricky sequence involving a timed mail delivery early in the game aside) fair, and don’t deserve to be spoiled by the likes of me.

Sorcerer shipped in March of 1984 in a box that was fairly plebeian for this era of Infocom. The crown jewel was contained inside the box this time, in the form of the infotater, an elaborately illustrated code wheel that was both one of Infocom’s most blatant uses yet of a feely as unabashed copy protection and so cool that it didn’t really matter. The infotater is today among the rarer pieces of Infocom ephemera. It remained in production for just a few months before Infocom switched to a standardized box format that was too small to accommodate it, and were thus forced to replace it with a less interesting table of information on plain paper.

Sorcerer sold decently, although not quite as well as Enchanter or the Zork games. (The steady downward trend in sales of Infocom’s flagship line of fantasy games would soon become a matter of increasing concern — but more on that in future articles.) Lifetime sales would end up in the vicinity of 45,000, with more than two-thirds of those coming in 1984 alone. It’s not one of the more ambitious games of Infocom nor, truth be told, one of the absolute best, but it is a solid, occasionally charming, playable game. If you find yourself in the mood for an enjoyable traditional text adventure that plays relatively fair with you, you could certainly do a lot worse.

(As always, thanks to Jason Scott for sharing his materials from the Get Lamp project.)

Steve Meretzky

August 26, 2013 at 8:52 pm

Well, gosh.

Allan Holland

December 1, 2018 at 6:21 pm

Steve, the fact that Jimmy uses the adjective Meretzkian says it all, as in “Meretzkian game design sensibility.” Sorcerer is a tour-de-force.

Lisa

August 27, 2013 at 6:57 am

You still have to sleep in Sorcerer, though, which can lead to some amusing results in certain locations or when you’re flying.

Duncan Stevens

August 27, 2013 at 6:20 pm

I seem to recall the infotater (in the standard gray box) coming in the form of a little booklet, not as fun as the code wheel but better than plain paper.

My favorite funny response from Sorcerer:

>WEAR FLAG

Who do you think you are, Abbie Hoffman?

Torbjörn Andersson

September 10, 2013 at 7:21 pm

My favorite was probably this one:

>FROTZ GRUE

There’s a flash of light nearby, and you glimpse a horrible, multi-fanged creature, a look of sheer terror on its face. It charges away, gurgling in agony, tearing at its glowing fur.

I’m sure I wasn’t the only one to find that immensely satisfying.

Sam Garret

August 30, 2013 at 5:06 am

I find it interesting to note that you place it as the lightest of the trilogy. De Gustibus and all that, but it was definitely my favourite. The complexity of the puzzles was sufficient that you really felt you had accomplished something when you worked it out (Spellbreaker seemed just arbitrarily cruel with puzzles divorced from a narrative arc, though it’s been a while so I may be misremembering from young teenage-hood), and if the ending happened a little abruptly, that was at least in part because I’d just been enjoying myself the whole way and didn’t want it to end.

Dave Thompsen

August 31, 2013 at 2:59 am

Sorcerer is still one of my all time favorite Infocom games, though I came at it in a bit of a round-about way.

The summer of 1984, I was twelve years old, I’d been saving my allowance, there was a computer store down the street, and so by gum, I walked down to buy the latest Infocom game myself, with my hard-earned moolah, after seeing it advertised in the latest New Zork Times.

So one afternoon I arrived home with my brand spanking new C64 copy of ‘Seastalker.’

Which I finished — that same night. Horribly disappointed, but having been raised on the torture of the Great Underground Empire, Seastalker was no challenge at all, and I felt somewhat cheated, not having really gotten the fact that it was an introductory adventure before plopping down my 45 bucks.

So the next day, amazingly, I managed to convince the guys at the computer store to let me return Seastalker, which probably makes me one of the few who actually managed to return an Infocom title.

To be fair, I didn’t get a refund. I got Sorcerer, the previously released title, instead.

This game I did not finish in one night. Probably took a couple of months.

I love it for so many reasons. First one I beat, myself. First game (and last, until many years later and the invention of eBay) that I had in the folio packaging, which I still have today, though the infotater’s a teeny bit worse for the wear. And the puzzles are brilliant — the completely fair and original maze, the sneaky old gnome, the potions – I loved them all. And the time travel puzzle is still, in my opinion, one of the most well-crafted examples ever seen in interactive fiction.

Thanks, Steve. Hitchhiker’s may have made me pull out more hair, A Mind Forever Voyaging made me think more, but Sorcerer? It set the hook and made me a fan for life.

Lisa

September 1, 2013 at 12:12 am

You solved Sorcerer by yourself at age 12? …wow. Props. I have never, never solved an Infocom game without help, although I think I did better than average on toughies like Hitchhiker’s Guide because I was familiar with the source material – though OTOH when I first tried Zork I, I was 6 years old and stymied by vocabulary problems like not understanding “ajar” (re: the window on the house). Still though. I was hopeless attempting these games even in my 20s.

(In fact I’m not sure there’s any IF or even graphic adventure game that I have solved without help, outside of the very simple games intended as parodies; despite my love of the genre I am, it seems, just really really bad at puzzle-solving.)

Dave Thompsen

September 1, 2013 at 1:32 am

To be fair, I’d started on the Scott Adams adventures on the VIC-20 when I was around 9 or 10, the the three Zorks for the Commodore a bit later, so I had a bit of practice.

Still, it took me a long time for Sorcerer. Spellbreaker, on the other hand — yeah, I needed a bit of a nudge on the 12 cube monstrosity, of which I expect Jimmy to get to in a couple of years.

John G.

November 21, 2013 at 9:04 am

Great articles, but Steve M. overrated as a writer? Come on, Steve Meretzky’s Rockvil is like Fernando Pessoa’s Lisbon.

DZ-Jay

February 21, 2017 at 10:24 am

Hi there,

Another great article and another brilliant description of an Infocom title.

There’s just one thing I’ve noticed in a few articles you’ve written already. The word “plebian” is a very common misspelling of “plebeian.” I know that the Interwebz are trying to normalize mistakes as just “evolving language”; but sometimes it’s just intellectual laziness. ;)

-dZ.

Jimmy Maher

February 21, 2017 at 10:59 am

Thanks!

Steve

April 9, 2017 at 6:32 pm

I wonder how much better the Enchanter games would have sold if they’d named them something along the lines of “Zork: Enchanter.” Sorcerer actually feels more like the original Zork than any of the games that followed, what with the sparse descriptions, giant underground portions with no thematic connectivity, and a “static” feel that makes the world feel cold and lifeless (the many “living” beings you come across are virtually indistinguishable from vending machines).

You are so dead on about the endgame. Neither Belboz nor Jeearr are mentioned from the moment you leave the Guild Hall until you stumble into the final room. The weirdest part is the amulet you get which is supposed to glow the nearer you get to Belboz (and does, if you happen to remember to examine it); it never factors into the game at all. [Though in retrospect, I wonder if it can help you decide which door to open when you near the end.]

The absolute worst part of the game is the sleep timer. It’s pointless. At least in Enchanter, the dreams gave you hints. Sleep serves no purpose in this game; you can pretty much type “SLEEP” at any time with no penalty (though I guess we should be thankful for this) and no other effect at all. The most ludicrous part is how short the timer is. In Planetfall, at least, the game acknowledges that different actions take a different amount of time. In Sorcerer (and Enchanted, for that matter), where every action is one turn, it feels like you are being forced to sleep every 5 minutes.

Also, they just couldn’t resist with their food & drink timers: after a certain amount of turns, the potion runs out! They sure loved their arbitrary and tedious play-time limits…

Joe

August 20, 2017 at 2:27 am

Years late, but I wanted to comment that you have not quite given Steve Meretzky enough credit. Sorcerer had to accomplish a task so vital that we don’t even think about it now: integrating the Enchanter and Zork series and mythologies.

Enchanter, as it was originally released, was not really set in the Zork universe. Sure, it was called Zork IV and had the adventurer in it as well as the death scene from Zork III, but it wasn’t “really” in the Zork universe. There were no grues, no mention of the Great Underground Empire. It was a new beginning in a new universe; bringing the adventurer in was just a way to say goodbye. (This, btw, is consistent with the original design notes. I suspect this was watered down a bit just before launch as the Zork books tied the series together explicitly.)

Steve had the challenge of integrating the Zork and Enchanter worlds, knitting together a consistent picture that retroactively made the games more connected. I think without his great love of Zork which shined through in every screen of this game, the rest of the series would have turned out quite differently. (Enchanter was retroactively integrated into Zork with the grey box re-release.)

Mike Taylor

September 19, 2017 at 11:58 am

Here are my own, rather less positive, thoughs on Sorcerer. I rate it a disappointing sequel, most importantly because the arbitrariness of the map prevents the story from feeling serious.

Jimmy Maher

September 19, 2017 at 12:18 pm

I don’t think our takes are that much different. I do find Sorcerer to be considerably weaker than Enchanter, and largely for the reasons you point to. Meretzky’s trademark gonzo humor has always been a little hit-and-miss for me, the writing isn’t always all that strong by any standard, and the game feels more like interesting bits sandwiched together than a coherent whole. (One part is actually a refugee from the old mainframe Zork, the last piece of same to be re-purposed by Infocom.) But I still find it well worth playing for some very good puzzles — I often prefer Meretzky’s puzzles to his humor — and to set up the final game in the trilogy, which is one of Infocom’s finest hours in my opinion.

Lisa H.

September 19, 2017 at 8:28 pm

Which area is from mainframe Zork?

Jimmy Maher

September 20, 2017 at 6:58 am

I admit I’m a little hazy on the exact details myself right now, but according to the third part of Tim Anderson’s “History of Zork” in the summer 1985 New Zork Times, the re-purposed puzzles were “the long slide and sending for the brochure.”

Mike Taylor

October 3, 2017 at 2:20 pm

Specifically: IIRC, sending for the brochure was the Last Damned Point in the mainframe Zork, while in Sorcerer it’s an absolutely crucial (and time-limited) part of the early game. And the part of the Sorcerer coal-mine where you climb down a rope to reach a room off the slide is lifted from mainframe Zork — though of course in Sorcerer it’s only one part of a much bigger puzzle.

Ben Bilgri

February 27, 2018 at 8:56 pm

“were part of an already burgeoning tradition” > “were part of an already burgeoning traditions”

Jimmy Maher

February 28, 2018 at 3:18 pm

Thanks!

Scott Hughes

January 21, 2021 at 12:52 pm

I recently discovered that Stu Galley lived about a 5-minute walk from my house, and that quite a few of my colleagues (I work at MIT) knew him from his work there after Infocom. That, plus COVID lockdown boredom, have inspired me to work through a bunch of the Infocom games I loved as a kid. One thing led to another, and I ended up finding this incredible collection of writings.

In reading these things while playing the old classics, I was very entertained by the fact that the spell for seeing the future in Sorcerer is called “vezza.” Given the role that Al Vezza played in the company and the “esteem” (ahem…) with which Meretzky held him, I’m a little surprised that the spell basically plays it straight.

Ben

April 11, 2021 at 7:43 pm

indeliably -> indelibly

two thirds -> two-thirds

Jimmy Maher

April 12, 2021 at 6:52 am

Thanks!

Vince

January 28, 2024 at 5:20 pm

Just finished it for the first time, it is probably my second favorite of the Infocom games I played so far, after Enchanter.

In general I agree with Jimmy’s take, Enchanter felt indeed tighter as a game, with a more cohesive setting and tone.

In Sorcerer, the map does feels a bit disjointed and some of the red herrings do feel like they are puzzles to be solved, like the ride, the stagnant pool or the haunted house.

But the puzzles themselves are excellent, the time paradox (Escape from Monkey Island has a similar one and they clearly took inspiraton from this game) ranks together with Enchanter’s maze as my favorites, and the glass cube is not too far behind. Also they felt quite fair, I solved it in a relatively short time with no hints needed.

Great game, recommended.